It was almost a year ago that I published a post laying out the difficulties of naming a brewery. Eleven months later, and with a bunch of new breweries popping up in New Zealand, none of which have ‘dog’ in the name, it’s high time we discussed the other side of the coin.

Beer names are an integral part of a brewery’s brand and identity. Just like a good brewery name, a good beer name attracts customers and ultimately, can sell more beer. And just like naming a brewery, there are certain pitfalls that brewers both young and old can fall into.

The advice I’m going to share with you is not meant as the be-all-and end-all, only a guideline. They’re my opinion only, and your gas mileage may vary. I have, however, built these guidelines over years of interacting with customers, and seeing what does and doesn’t seem to work. Of course, no offence to any brewers I use as examples. It doesn’t reflect on the quality of your beer, and if you’ve been calling your beer by a certain name for years, I am by no means suggesting you change it.

I realise I’m starting with a rule that’s incredibly difficult to define. What makes something catchy? Seems like almost a “I know it when I see it it” situation. But let’s take a stab at defining it anyway.

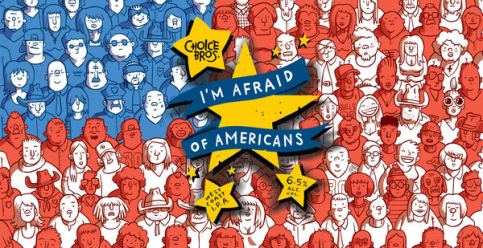

A good place to start is keeping it short and simple. Beer names can be longer than brewery names, sometimes substantially longer. Choice Bro’s I’m Afraid of Americans would be a good example of a long name that I think works (we’ll get to why names work soon).

But there is always a limit, and in my experience, if a customer can’t pronounce and/or remember the whole name of a beer from the time they’ve read the menu to when they make it to the bar, they’re less likely to order it or recommend it to a friend. The Moon Dog/Yeastie Boys collaborative beer Peter Piper’s Pickled Pepper Purple Peated Pale Ale (AKA The 7 ‘P’s) suffered from this.

Beyond keeping it short, what else can make it ‘catchy’? Hard to say. Poetic devices tend to help. Things like rhyming, assonance, alliteration and consonance can help. Names like Pils ‘n’ Thrills, Double Trouble, Red Rocks Reserve, Sauvignon Bomb employ these devices.

Likewise, humour can be a great tool for naming beers. In my experience, people can remember jokes easier than names. Puns and in particular beer-related ones, are often popular – like Four Horsemen of the Hopocalypse. But humour can be a double edged sword. Which brings me to…

2. Keep it Classy

Beers do need to be named in a manner that make them sound appetising. You might think it’s really funny to name your Porter with cacao nibs ‘Chocolate Starfish‘ (and so might your close friends), but be warned, a lot of people will be put off by the name and/or assume your beer literally tastes like arse. Also, I’m going to assume the people making/naming the beer are exactly the kind of horrific Dudebros we’ve all spent so long trying to exorcise from our industry and community.

Simple crassness aside, keeping it classy is a good principle to guide not only naming, but all sorts of branding and marketing decisions. I’m talking about controversy here. Stirring up controversy with a name that could be (or just is) sexist, racist, homophobic, etc. may be a cheap way to get media attention short term, but is a bad foundation for building a long-term customer base.

I won’t go into detail but I think we all know of breweries that have adopted this technique in the past. Ask them how it’s gone. Or I suggest reading Jim Vorel’s really excellent piece on the subject.

3. Themes are Good. sometimes.

Many breweries have themes to name their beers. For example Choice Bros. Uses Bowie lyrics. Panhead has a hotrod motif (Super Charger, Blacktop, Boss Hog and so on), whereas Bach Brewing uses a beach theme in their beer names (Crayporter, Kingtide, Driftwood). Themes can be a great way to get build a consistent brand across a range of beers and in your customers consciousness. But they can get you into trouble in two different ways.

The first is slavish adherence. Breweries who stick too closely to a naming theme can end up painting themselves into a corner. ParrotDog for example, used almost exclusively dog or bird themed double-worded names for their beers (BloodHound, DeadCanary, BitterBitch). But coming up with names that fit that scheme is difficult, and we gradually saw them shift away from it with names such as RiwakaSecret, Pandemonium, and the RareBird series. Coming up with new beer names is hard enough, and imposing arbitrary restrictions on yourself only makes it harder.

The second way naming themes can get a brewery into trouble is when they make each of your beers essentially indistinguishable. For a really great illustration of this, we need to look overseas. Russian River, from Santa Rosa California. Their Barrel Aged/Belgian inspired range all have names that end in ~tion. As in: Redemption, Consecration, Damnation, Sanctification and so on. Now I’ve had a decent number of these beers, but I couldn’t tell you which ones. They’re all really excellent beers, but they’ve all sort of blended into one in my memory.

Likewise when naming beers, numbers are not your friend. Founders for example, uses years to name their beers – 1946, 2009, 1854, and so on. Again, I’ve had all of them, but could I tell you which one’s which? Nope.

4. Does it Do What it Says on the Tin?

In point five of How to Name a Brewery, I elaborated on the need to choose adjectives carefully – if you use an adjective in your brewery name that could theoretically apply to beer – a flavour, colour or aroma, customers will assume that it applies to your beer.

Now forgive me if it seems like I’m stating the obvious, but this principle applies doubly to beer names. The reason I am stating the obvious is that breweries still do it with surprising regularity. Infringements on this principle can be relatively minor – for example Townshend Black Arrow Pilsner which customers occasionally mistake for a dark beer, but because of the word ‘Pilsner’ mostly gets away with it. But sometimes a misplaced descriptor can cause real havoc with customers.

I still have vivid memories of pouring a beer at Hashigo (quite a few years ago) that committed this sin – Liberty Brewing Sexual Chocolate1. Sexual Chocolate was a beer that, although somewhat sexy, was not very chocolatey at all (it was a hoppy Brown Ale). Customers would order a Sexual Chocolate, and then almost immediately return it, claiming I’d poured the wrong beer: they were expecting a chocolate porter.

Eventually I started warning customers: “this beer is not very chocolatey, do you want to try it before you order?” If your beer needs to come with a disclaimer, then you should probably reconsider the name. I like to call this the ‘Does it do What it Says on the Tin?’ test.2

So let’s review. You’ve brewed a beer, picked out a name that’s short, punchy, uncontroversial, and accurately sells the beer’s attributes. But you’re not there yet, you have to do one more thing.

5. Google It

Maybe I should really say Untappd it, but either way, check to see if any other brewery is using the same name. On this one I’m talking from experience. Many years ago, I made a video of a collaboration brew between Garage Project and Nøgne Ø Brewery. The beer needed a name and I suggested Good as Gøld, without checking it on Untappd or RateBeer. Silly me, because it already existed. I really should have checked.

Stouches over names are fairly infrequent, but double-ups can happen quite often. If a name seems absolutely perfect, there’s a good chance that someone else has got to it before you. Which isn’t to say that double-ups are necessarily a disaster. If a little brewery in another country that will never ever be seen in New Zealand is already using a name, then go right ahead anyway. But if it’s another NZ brewery using it, you need to start again, out of courtesy if nothing else.

It is, however, a different matter if it’s a really famous or iconic beer from another country. If an NZ brewery ever dared to name a beer, ‘Pliny the Elder’, ‘Heady Topper’, or ‘Sculpin’, then they fully deserve to be dragged over a bed of hot coals.

If a brewer ever wants to run a name past me, feel free. You can reach me on twitter any time.

NOTES

1. There seems to be no record of this beer online except in DEEP in Hashigo’s newsletter archives. ↑

2. Strangely enough, Yeastie Boys did the exact same thing with their beer Kid Chocolate, which had almost nothing chocolatey about it at all. Yes, that was released seven years ago. I have a long memory and I’ve been doing this for a long time. ↑

Ha. Peter Piper’s Pickled Pepper Purple Peated Pale Ale is a perfectly memorable name! Maybe we need a Woodchuck named beer along the lines of “how much wood would a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood”?

I was at that beer launch – I could also cite it for breaking rule #4 for not being purple… ;P

Pingback: So you want to start a brewery… – The Brewer's Daughter

I’ve got a name for a new beer.How can I get beer companies to buy it?

Honestly, I don’t think you can. You could Trademark it (or whatever the equivalent in your territory is). And then try to convince a brewery to buy that trademark. But names are potentially limitless resource. Rather than pay, most breweries will probably find another name for free.