On Friday February 19 it was announced that Blenheim based Moa Brewing was to be sold. This was not exactly a surprise to a lot of people. For reasons that will become clear, many people had speculated that Moa was at least passively seeking a buyer, and had been doing so for quite some time. What was surprising was who bought it and for how much.

Current Moa CEO Stephen Smith has bought the brewery via his company Mallbeca Limited for $1.9 million, which is (and this is the technical term), a pittance. By my reckoning, the value of the site the brewery sits on must account for a decent chunk of that $1.9 mill. Factor in the other assets – the brewery plant, the taproom and stock on hand (including a barrel program), and the sale price would seem to barely cover the physical assets of the business. What this makes clear is that the Moa brand and all its associated ‘goodwill’ has been sold for essentially nothing.

When Moa floated their IPO in 2012, they offered 12 million shares at $1.25, representing 37% of the company. By my math, that valued the company at $40.5 million. This begs the question: How can it be sold for less than 1/20th of its value nine years later? What the hell went wrong?

The answer is not entirely straightforward. There were a string of strategic decisions and occurrences that lead to Moa’s downfall in my opinion.

Let’s go back in time to 2010. Moa is a small brewery run by Josh Scott, son of notable winemaker Alan Scott. In August of that year the company was bought into by The Business Bakery, an investment firm started by Geoff Ross, flush with money from the sale of Ross’s vodka brand, 42 Below. This was widely discussed in beer circles at the time, but didn’t make much of a splash in the media. The only article I could find referencing Ross’s buy-in was this one, about a queer-phobic marketing campaign the brewery ran. Which is funnily enough, the harbinger of what was to come.

In researching this article, I found myself deep in Moa’s social media feed. The change in tone from pre-Ross involvement is stark. For all of 2010, through to September most of Moa’s Facebook photos are of their products, their brewery, the fit-out of their tasting room and Josh Scott knocking about having a good time. Come November, they launch a new t-shirt promotion:

I’m not going to re-litigate the banal bigotry of this campaign. What I will say is that it didn’t feel like the Moa we knew. It felt different and it felt ugly. Scott distanced himself from the campaign:

Moa Brewing Company director Josh Scott, of Blenheim, said he knew nothing of the marketing campaign until he saw posts about it on the internet.

“Absolutely not. We have a whole Auckland office now.”

Source.

That line is telling: this change of course wasn’t coming from the brewery. It was coming from the Auckland marketing team. Moa didn’t continue the campaign, but they didn’t exactly distance themselves too far from it either:

Moa Beer marketing manager Sunil Unka, of Auckland, was unavailable for comment yesterday, but a spokesman told gayNZ.com the company was concerned the campaign had offended gay people.

Moa had not received any direct complaints about the T-shirts, but has offered to send some to the organisation.

Source.

Tellingly, Moa did not remove any of the posts from their Facebook. They would also post pictures of Moa employees wearing them a year later.

The low-carb campaign signalled a change in direction for Moa. But this change didn’t really kick into top-speed until they launched their rebrand in 2011. The change in the tone of their Facebook is abrupt. Looking back at their feed, you can almost hear the gears grind as they change direction.

The decision to rebrand was outwardly a good one. Moa’s identity up to that point had evoked it’s winemaker heritage and it was somewhat fragmented and kind of stuffy. By contrast, the new brand was modern, sleek and fairly well integrated:

The problem wasn’t with the rebrand itself, rather the marketing strategy that came with it. I would describe it as a three pronged approach:

- Target a male audience.

- Make the Moa brand as visible as possible.

- Focus on the export market internationally and the supermarket trade locally.

In each one of these points, we can see a piece of Moa’s downfall. Let’s start with the first one. Moa’s decision to target an exclusively male audience was immediately clear from the get go. In 2011 shortly after launching their new brand, Moa put out a series of online ads, explicitly appealing to men. Here is a representative sample:

On the surface, a brewery appealing to a male audience might make sense. After all, it’s what most mainstream, corporately owned breweries do. Is not the Speight’s Southern Man one of the most iconic kiwi beer ad campaigns ever?

The thing is, targeting such a select audience is something most ‘craft’ breweries don’t do. There’s nothing overtly masculine about Garage Project or Parrotdog. Even Panhead, a brand which evokes traditionally masculine tropes such as motorcycles and hot-rods, doesn’t do so in a manner that explicitly excludes women as a consumer. But that was the approach Moa took. And spoiler alert here: Panhead is going to come up a lot in this story.

What I would call Moa’s latent misogyny became straight-up overt misogyny when they prepared to float the company on the share market, and launched their Initial Public Offering (IPO). This was essentially a prospectus to potential investors, the full title of which was (and I wish I was kidding): “Moa Group Limited Initial Public Offering Investment Statement: Your Guide to Owning a Brewery and Other Tips For Modern Manhood”.

A huge quantity has been written about this document. For a rundown of the highlights, including the full PDF of the IPO, I recommend reading this post on The Beer Diary. The only mention of women as potential consumers (not even investors) is in the whole document is in this section here:

Brewers find cider is popular with female and gluten-free consumers. These groups are often complementary to brewers’ traditional sets of consumers and present a new market opportunity.

Moa IPO, p.91

Most explicit of all was this quote from an article which interviews Ross about the document:

[Ross] said the prospectus was targeted at Moa’s prospective investors who were largely the same demographic of young and middle-aged, aspiring, affluent men who drink the product.

Source.

Where this is all a strategic blunder is that it sections off the potential market for Moa beer into a needlessly small demographic. Sure, some women (and other people of different gender expressions) wouldn’t care, but others would and as a result, have since declined to purchase Moa’s products. They’ve been alienated for essentially no real gain to Moa.

This brings me to the second part of Moa’s marketing strategy: making Moa as visible as possible. There are two parts to this plan, the first of which ties into their choice to market to a male audience: Controversy for controversy’s sake.

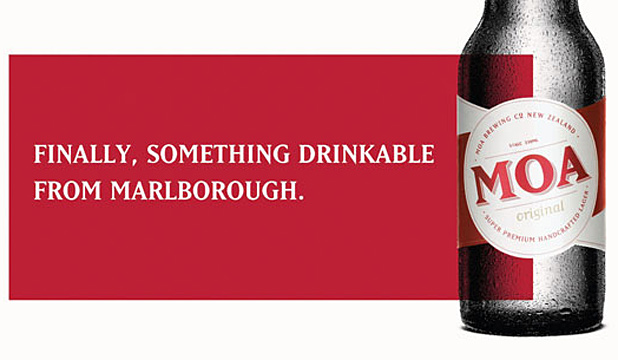

If you think the low-carb campaign and the IPO were the only time Moa courted controversy, you’d be very wrong. Over the years, there was a cavalcade of needlessly provocative advertisements. It started with the “Finally something drinkable from Marlborough” ads:

What was on the surface a cheeky dig at wine producers (including Josh Scott’s father and the winery that made Moa possible), was also something of a middle-finger at other Marlborough breweries, such as Renaissance.

Then came the awkward flirtation with gang imagery, including (briefly) naming a beer ‘Black Power‘, a gang-patch style logo, and bizarre, black power themed tap handles that looked very much like l sex toys:

Then there was the bafflingly non-nonsensical return to homophobia:

The absolute peak of bullshit controversy-seeking would be the infamous Pakistani Backhander campaign, which I’m not even going to share here (you can find images of it online if you want). Suffice to say, it blended pretty overt racism with again, some weird homophobia, by way of a crude Photoshop job.

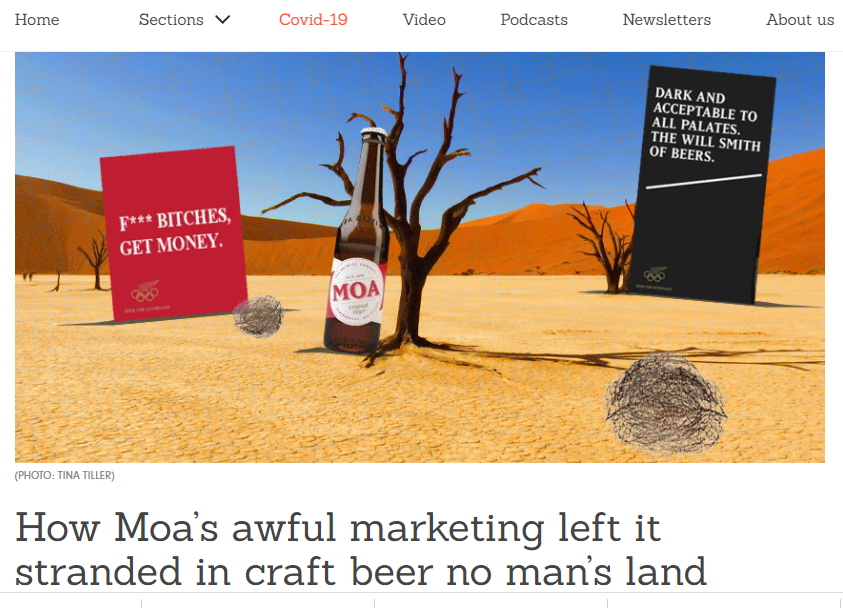

And I’m only scratching the surface here. There were many more posts and campaigns designed to garner the brewery attention, which failed to take off. It got so ridiculous that at one point I wrote a parody Moa campaign, which was taken by several readers at the time to be the real thing. As a weird coda, it accidentally found it’s was into a Spinoff article on the same subject as this very post!

Now there is an adage “There’s no such thing as bad publicity”. Geoff Ross clearly subscribes to this belief:

With recent newspaper headlines such as “Breakfast beer slammed by critics”, “Cashing in on wine’s good name” and “Gay community offended by Moa Beer campaign”, it’s a good job Moa’s new boss, marketing guru Geoff Ross, believes there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

In his book, Every bastard says No, the man who gave the world 42 Below vodka and is now backing Moa gives his key insights into successful marketing.

High on the list is “At all costs get noticed. Be heard. Stand for something”. Judging by the amount of news coverage Moa has been attracting in recent weeks I’d say he’s doing a very good job!

Source.

As someone who was working on the front-lines of craft beer at the time this was happening, I’d have to disagree. The abrupt change left a bad taste in many mouths. It was cheap, inauthentic and ugly, the exact opposite of what we knew and loved from Moa. The end result was that they lost some important customers.

Myself and a lot of my friends stopped buying Moa, and we told our friends not to buy it either. Both bars I have worked at declined to pour Moa beer. I know other bars around the country did the same. As a result, Moa alienated the very people who had up to that point been their biggest evangelists: existing craft beer drinkers. Now hold onto that thought because it’s going to be relevant again later.

For now I want to change course and talk about the other important aspect of Moa’s strategy to increase their brand visibility – sponsorship.

Post Ross’s buy-in, Moa embarked on a staggering amount of sponsorship campaigns: music festivals, dirt biking, showjumping, golf, yacht racing, a rabbit hunt, the Olympics, a trip to Antarctica, The Americas Cup. If they could put their logo on it, they did:

Scrolling through Moa’s Facebook, one of the things that struck me was the literal millions they spent on sponsorship over the years. Now sure, you’ve got to speculate to accumulate. But at the same time, the company posted years of multi-million dollar losses starting in 2012 right up until 2020. Moa losses were such an industry talking point that local satirical site Too Much too Beer wrote a piece about it. With the company losing millions annually for nearly a decade, it begs the question: Maybe you should’ve sponsored fewer yachts?

All this very expensive promotional work realistically was in service of one thing; our final prong of the business strategy: focusing on export and supermarket trade. Right from the get-go, Ross let it be known that he wanted Moa to be New Zealand’s foremost beer-brand internationally. In an interview with interest.co.nz, he said the following:

Every country has an iconic beer brand and we want Moa to occupy that space in the future. Right now there’s clearly a gap in the market for a beer like ours and we believe the combination our branding and our brewing technique to create a high quality product with a long shelf life are what sets us apart. So we think we have all the founding principles to create a really iconic international beer brand right here in NZ.

Source.

…

While we do want broad consumer recognition domestically I would prefer to achieve the sort of success and positioning that Cloudy Bay has gained for itself where around 80% of its product is exported but it is also highly regarded domestically. So in an ideal world we want Moa to become the Cloudy Bay of craft beer.

Ross wanted Moa to not just recognised, but the most iconic beer in New Zealand. That means one thing: unseating Steinlager, something acknowledged in the same interview:

“While Steinlager has achieved some good success previously, there’s always been the problem with the German name and their primary focus has been principally on the domestic and Australian markets. For us it’s the reverse. We see the US & UK as our primary markets because that’s where the growth will come from while simultaneously retaining a strong focus on our domestic market here.”

Source as above.

…

So while Steinlager may have once conceived that catchy positioning line “… they’re drinking our beer here” the phrase might be more appropriately attributed to Moa in the future if those backing its high profile listing have their way.

First off, relying on export of beer is an inherently risky proposition. Beer is a lot less stable than wine – it’s more heat sensitive, and has a shorter shelf-life. Selling overseas involves a lot more effort too. Invariably a distributor is needed which involves slows down the whole process and adds an extra company taking a cut of the profit. Ross repeatedly mentioned the US market as a goal. What any beer geek could have told him at the time was that selling beer to the Americans is very much selling sand in the desert.

Export markets are also very fickle. I’ve seen on multiple occasions, breweries offering substantially discounted beer to the New Zealand market when export orders consisting of whole container loads are cancelled at relatively short notice. So while many ‘craft’ breweries do export beer to one degree or another, I struggle to name any brewery that relies on it to the tune of the 80% mentioned by Ross.

Indeed Moa quickly came to realise this, and by 2014 were discussing difficulties with the US market. This in some ways is what precipitated the shift to the local supermarket trade. And around this time, drinkers would have seen a lot of very cheap 12 packs of Moa Methode. By 2016, Moa were proudly claiming to have 11 percent of the supermarket trade.

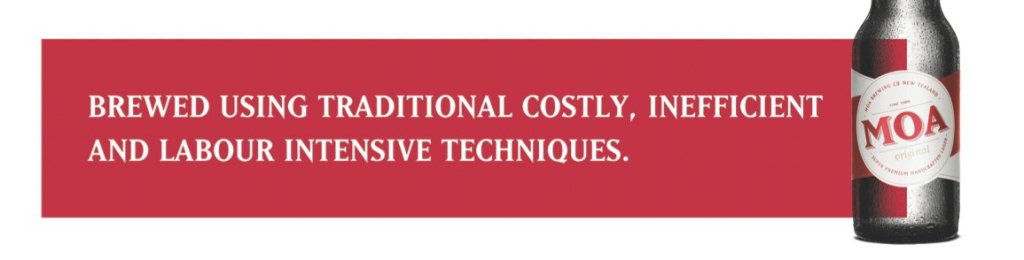

Here’s the thing about supermarket beer sales: They’re inherently high-turnover with low margin, particularly when you’re dealing with the bulk, 12 pack lager market. Most people shopping in this segment will buy whatever is on special. By focusing on this sector, Moa was directly going up against Lion and DB, in what is essentially a volume game – who can sell more, cheaper. The problem for Moa is fairly succinctly summed up in one of their own (and frankly better) ad campaigns:

That’s a fairly accurate picture of the situation for Moa. They were attempting to go toe-to-toe with Lion and DB on their own turf. Lion Nathan (owned by Kirin) is the biggest producer of alcoholic beverages in the country and it’s primary production facility The Pride produces hundreds of millions of litres of beer every year, and DB, owned by Heineken is not far behind. Moa was never going to win that fight.

While cracking the off license market is really important, and has been pivotal to the success of breweries like Parrotdog, Garage Project and Panhead, those breweries also worked hard to maintain their ‘craft’ beer bona fides.

Remember how I mentioned the Moa had alienated a decent chunk of existing ‘craft’ beer drinkers, including several who owned or operated bars? Well those relationships are actually quite important. A busy on-license, even one that rotates its taps can turnover tens-of-thousands (if not hundreds-of-thousands) of dollars of beer from a single brewery. What’s more, on-license sales can often drive higher off-license sales. After all, drinkers are less likely to invest in a 12 pack of a beer they’ve never had. But that reticence isn’t so high when it comes to buying a single beer in a bar. So if a customer enjoys a beer in a bar, not only are you building a stable relationship with on-license customers, your investing in future supermarket sales later on.

So while the aforementioned Parrotdog and co were working hard to sell in supermarkets, they never forsook the traditional ‘craft’ beer on-license trade. This is something Moa kind of came to realise down the line. At the 2019 investor AGM, Ross said this:

Selling beer at the supermarket isn’t a magic bullet and doesn’t drive gross margin.

Source.

Moa would go on to invest in various Auckland hospitality businesses by purchasing the Savour Group, and when it came time to shear-off the unprofitable brewery, the Moa Group essentially morphed into a hospitality company. Or if I was being cynical, I’d say the corporate leadership transplanted themselves onto profitable hospo co, throwing the brewery under the bus, but I digress.

At this point, the picture should be pretty clear: Moa was spending a lot of money on their brand, investing very heavily in anything that would raise their profile but they were not actually building a stable, sustainable or even particularly functional brewing company. Nor do I think they really ever intended to.

To say they were intentionally losing millions of dollars a year wouldn’t be accurate. Rather I’d say they didn’t mind sustaining those kinds of losses for the first few years because they didn’t intend to be running Moa for very long. I believe that from very early on they planned to sell the Moa to one of the larger brewing companies. After all, this is exactly what happened with the company that made Ross a multi-millionaire: 42 Below Vodka.

I don’t want to go too deep into the history of 42 Below, least we get sidetracked. You can read all about it in Ross’s book. I will say Ross did start it from scratch in 1998, and that hard work and achievement deserves acknowledgement. Having steadily grown the business for seven years, the company was sold to Bacardi for $138 million.

What is pertinent about 42 Below is how they marketed it: controversy. Oodles of it. As much as they could get. And that was fine for selling vodka, but ‘craft’ beer is a different game. For starters and as I mentioned, beer is an unstable product. Make too much and you either have to unload it cheap, or pour it out. Make too much vodka, and it will keep literally forever.

What’s more, and this is where we’re really getting to the crux of what went wrong for Moa, 42 Below was essentially the only vodka game in town at the turn of the millennium. By contrast, Ross was stepping into an already crowded beer market. The same year Moa launched their IPO, Lion was already making their first modern craft beer acquisition – Emerson’s Brewery.

The sale of Emerson’s to Lion for $8 million may well have spurred on Moa, After all, they’d shown they were keen to acquire independent brewers. Why couldn’t Moa also attract a multi-million dollar deal from the brewing giant? The trouble is, while they were busy tarting themselves up and making eyes at Kirin, something else was coming up behind them. Something unstoppable, powered by a supercharged-V8 engine, and going a million-miles-a-minute: Panhead.

To say Panhead killed Moa would be an exaggeration. After all, Moa died a death of a thousand cuts. But the story of Panhead must be a cut felt particularly deeply. Started in 2013 by former Tuatara brewer Mike Nielson, right out the gate their popularity and growth was staggering. The flagship beer, the very hoppy Supercharger APA was the darling of the Wellington ‘craft’ beer scene, but was also one of the first hoppy beers to find huge popularity with everyday drinkers. I vividly remember a customer coming up to the bar, circa 2016 and saying “I don’t like craft beer… do you have Supercharger?” When GABS launched their annual Hottest 100 Kiwi Craft Beers List, Supercharger came top in 2016, 2017 and 2019, as well as 3rd in 2018 and 4th in 2020.

Panhead galloped away and was sold to Lion in 2016, only three short years after it’s founding. The total sale price was $25.1 million. Lion described Panhead as “a runaway train” and “[Panhead] can’t keep pace with demand.”

Now where all this is a problem for Moa, is that it effectively took Lion off the table as a prospective buyer. After all, why would they want to buy an unpopular and unprofitable brewery when they already had two very successful brands in their portfolio?

OK, there’s also DB, New Zealand’s second largest beverage producer. Well, in 2011 they had started their own faux-‘craft’ label, Black Dog Brew Co. to moderate success. Then in early 2017, they bought Tuatara Brewing for $30.2 million, effectively taking them out of the equation as well. This left pretty few options for Moa.

There was always Independent Liquor (owned by Asahi). They had bought Duncan’s Founders in 2012. The success of that acquisition has always seemed somewhat flat. While Founders has become a supermarket staple, it’s never quite risen to the prominence of even Independent’s other faux-‘craft’ label Boundary Road. Independent has not made any moves that would indicate they would want to buy another brewery ever since.

After that, the field gets kind of thin. There was Constellation Brands, a massive American brewing concern with a subsidiary in New Zealand. They bought San Diego based brewery Ballast Point for a staggering US $1 Billion in 2015.

Indeed for a hot minute, it looked like something might be happening there. A distribution deal was set up in 2018 that would see Moa distributing Ballast Point in New Zealand. There was talk this could presage an acquisition. Come 2019 though and supermarkets were selling short-dated cans of Ballast Point at heavily discounted prices. Later that year, Constellation would unload Ballast Point to a virtually unknown brewer in Illinois for a measly US $8.55 million, in a move somewhat reminiscent of Moa’s sale this year.

At this point, things were looking dire. There was always Coca-Cola Amatil. They had bought Feral Brewing in Western Australia. Might they want to get into the New Zealand beer game? Well they did, by signing a distribution deal with relative newcomer Fortune Favours in 2019.

The clock was ticking. Every year Moa went unsold, they racked up multi-million dollar losses and options to sell were running out. Moa had built an essentially toxic brand. Their turnover was high-volume, low-margin and their primary customers were fickle supermarket lager drinkers, more interested in value than quality or loyalty. They were bleeding money and their list of potential buyers was looking very short. It’s not impossible that there was still someone out there that might wish to acquire a New Zealand brewery, but even then Moa probably wouldn’t be top of that list.

Then Covid-19 arrived and the world changed. With massive global uncertainty, it’s hard to imagine any company wanting to shell out tens of millions to acquire a struggling brewery. I have to suspect the global pandemic was the final nail in the coffin. Moa had to be cut loose, lest it bleed them dry. Which brings us up to today.

Moa’s future is uncertain. It may rise again under new ownership, maybe it will go back to it’s regional roots and be just another local brewery. Or possibly will fade away like its extinct namesake. I do know that the former Moa Head Brewer (and top-bloke) Dave Nichols departed the company late last year to start his own brewing operation in Marlborough. I greatly look forward to what develops there.

I often like to wrap up my writing with a “what did we learn?” reflection. Looking back I think Moa’s strategy was a poor one from the start. Getting to the point where you could be sold should never have been the goal. Building a stable, sustainable business should have been their primary aim. If they had maintained their integrity with the existing ‘craft’ beer market and used that as a foundation for their growth, things may have panned out differently. To that end, perhaps the takeaway should be “don’t be a dick?” It would be a fittingly kiwi lesson. That, and perhaps “sponsor fewer yachts?”